Importance of evaporation

Recognition of the importance of evaporation has become more pronounced in time. Weather patterns are changing and with the recent droughts in Europe, the problems of too little water became eminent: forest fires, erosion, irrigation prohibitions for farmers resulting in lost or reduced yield, low river water levels that affected shipping, and drinking water companies that asked their consumers to reduce their demand during peak hours. Also, electricity companies that could not cool their installations, and thus risking an unstable energy grid. Finally, water quality issues arose due to high water temperatures. For low-lying countries like the Netherlands, the recent droughts also created problems due to salt water intrusion and the associated salty seepage affecting crop yield. Additionally, such countries encounter also a long-term effect of droughts: subsidence causing settling of houses. Hence droughts have major consequences for the economy, nature and agriculture, and also directly affect human well-being.

To better tackle these problems, proper decision-support systems are required: models that enable decision makers (e.g., water resources planners, waterboards, drinking water companies) to have up to date information about the quantification of surface runoff, the soil moisture budget, transpiration, recharge and groundwater processes in their command area. To achieve this, an accurate representation of the largest water consumer -evaporation- is essential. However, despite being a key component of the water balance, evaporation figures are usually associated with major uncertainties (10-50%) as this term is notoriously difficult to measure or estimate by modelling. Errors in the estimation of evaporation will propagate to estimates of related processes, such as the soil moisture budget, recharge, groundwater processes and ultimately river discharge. Moreover, a large part of the solar energy is used for evaporation, due to the large latent heat of water (evaporating 1 kg of water requires 2.25 kJ of energy). Therefore, evaporation is a pivotal element of the surface energy balance, which drives thermal convection in weather systems. Apart from this energetic aspect, atmospheric models see the available water (evaporation, soil moisture content) as water provider and use it as their boundary condition for moisture input. Errors in this boundary condition, leads to erroneous weather forecasts, which has direct consequences for the performance of the hydrological models due to errors in precipitation, temperature, wind, etc. Hence evaporation and its related energy fluxes (sensible and ground heat flux) are important for both hydrologic and atmospheric sciences, and thus a better representation of the land-atmosphere interface is essential.

Challenges

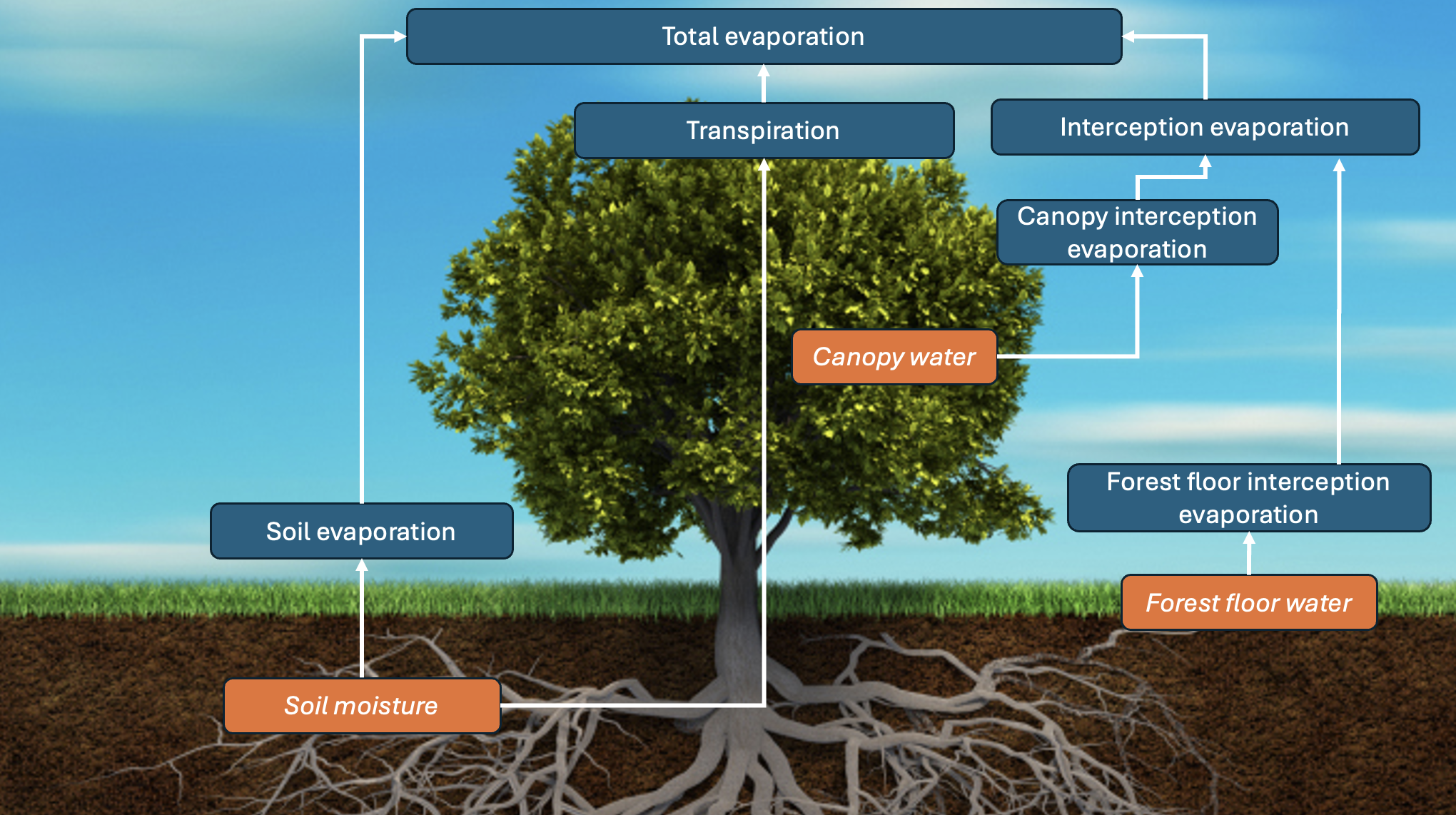

The main objective of my research line is to increase our understanding of evaporation and the related surface energy balance. To meet this objective three challenges, have to be tackled: 1) accurately quantifying evaporation by observations in different land use settings; 2) defining how total evaporation is partitioned into separate evaporation components, i.e., interception, soil evaporation, and transpiration; and 3) spatiotemporal upscaling of the results to field, regional or global scale.

1. Quantifying evaporation. Despite the importance of evaporation, not many observation stations exist. Worldwide there are over 67,000 rain gauge stations and 9,000 runoff stations, against only 439 evaporation flux towers. This limited number of measuring points results in a limited understanding of the spatial and temporal patterns of evaporation. This is especially true considering the large diversity in land use types, such as forests, agriculture, pastures, and urban areas. Existing techniques to measure evaporation, such as eddy correlation systems or scintillometers, are expensive and, more importantly, are not always applicable in all land use settings due to footprint issues (i.e., area from where water vapour originates), non-closure of the energy balance, heterogeneous land surfaces, sensor sensitivity, and required non-trivial correction factors.

2. Evaporation partitioning. Knowledge on how total evaporation is partitioned into transpiration (i.e., water used for plant growth), interception (wet surface evaporation), soil, and open water evaporation is of utmost importance for water management practices, irrigation scheme design, and climate modelling. Especially for modelling purposes, this information is crucial due to differences in time scales of the different evaporation components (e.g., transpiration is a monthly process and interception a daily). If observations of total evaporation are already limited, observations on the separated evaporation processes are even scarcer. Even if available, observations are often highly uncertain, due to measuring difficulties such as instrument resolution, and underlying measuring assumptions. This causes the magnitude of the ratio of transpiration to total evaporation to still be under debate.

3. Upscaling. The landscape is highly heterogeneous with patches of grass, forest, agricultural field, urban settings, etc. Often satellite information is used to cope with this spatial variability once the patch size is larger than the grid size of the satellite resolution. Although it seems that these satellite products incorporate the spatial variability correctly, one should be aware that these satellite products often derive evaporation from observations of surface temperature (thermal imaging) in a very indirect manner. Often poorly validated model concepts with grid-average parameters are used (see point 1). The validity of these concepts is questionable, because sub-grid processes like advected energy and lateral flow are neglected. Hence the soil-vegetation-atmosphere continuum cannot be seen as an exclusively vertical process, as assumed. Additionally, also within one land use type, spatial differences occur where both water and energy fluxes are spatially not homogeneous (e.g., soil and vegetation heterogeneity, vapour plumes).

Also, temporal upscaling is difficult due to differences in time scales per evaporation type. As an example, interception evaporation is a quick process whereby the wetted surface (i.e., the interception storage) is often emptied within one day. On the other hand, transpiration has a much longer time scale: plants can continue to transpire for months before the wilting point is reached. This suggests that interception should be measured and modelled on the daily time scale to incorporate all temporal dynamics, whereas transpiration measurements and modelling can be performed at the monthly time scale.

Speulderbos (The Netherlands)