Interception is the amount of rainfall, which is ‘intercepted’ and will not infiltrate into the ground or take part in the runoff process. The intercepted rainfall will stay for example on leaves, in the top soil, in small pools on roads or on roofs, etc. and will evaporate within a few days. Evaporation from interception has often been disregarded in hydrological modelling. Reasons for neglecting interception are that the amounts involved are considered small and that it is difficult to measure interception accurately. However, it appears that interception can amount to 20-40% of the precipitation. If interception is disregarded in hydrological models, it will be compensated by another process of the hydrological cycle to meet goodness of fit criteria. This jeopardizes the physical representation of the hydrological model with all its related possible errors.

Moreover if interception is taken into account; it is often considered a constant. Although this is better then completely disregarding interception, the interception process is far from constant and varies in time and space. This is one of the main reasons why measuring interception is difficult.

For the latter I developed a special device to quantify forest floor interception. I investigated interception evaporation on several locations:

- Huewelerbach catchment, Luxembourg: beech trees and forest floor

- Westerbork, The Netherlands: grass/moss

- Botanical garden Delft, The Netherlands: Cedar needles

- Harare, Zimbabwe: Msasa leaves

Canopy Interception

Canopy interception is the rainfall that is intercepted by the canopy of a tree and successively evaporate from the leaves. Precipitation that is not intercepted will fall as throughfall or stemflow on the forest floor.

There exist a lot of methods to measure canopy interception. The most often used method is by measuring rainfall above the canopy and subtract throughfall and stem flow (e.g., Helvey and Patric [1965]). However, the problem with this method is that the canopy is not homogeneous, which causes that it is difficult to obtain representative throughfall data.

Another method that tried to avoid this problem is applied by e.g., Shuttleworth et al. [1984], Calder et al. [1986], and Calder [1990]. They covered the forest floor with plastic sheets and collected the throughfall. The disadvantage of this method is that it is not suitable for long periods, because in the end the trees will dry due to water shortage, and the method is also not applicable for snow events.

The method by Hancock and Crowther [1979] avoided these problems, by making use of the cantilever effect of branches. If leaves on a branch hold water, it becomes more heavy and will bend. By measuring the displacement, it is possible to determine the amount intercepted water. Huang et al. refined this method later in 2005 by making use of strain gauges. However, the disadvantages of these methods are that only information about one single branch is obtained and it will be quite laborious to measure an entire tree or forest.

Forest Floor Interception

Forest floor interception is the part of the (net) precipitation that is temporarily stored in the top layer of the forest floor and successively evaporated within a few hours or days during and after the rainfall event. The forest floor can consist of bare soil, short vegetation (like grasses, mosses, creeping vegetation, etc.) or litter (i.e. leaves, twigs, or small branches).

In the literature little can be found on forest floor interception, although some researchers have tried to quantify the interception amounts. Generally these methods can be divided into two categories (Helvey and Patric, 1965):

- Lab methods, whereby field samples are taken to the lab and successively the wetting and drying curves are determined by measuring the moisture content.

- Field methods, whereby the forest floor is captured into trays or where sheets are placed underneath the forest floor.

An example of the first category is of Helvey (1964), who performed a drainage experiment on the forest floor after it was saturated. During drainage the samples were covered and after drainage had stopped (assumed 24 h), the samples were taken to the lab, where they were weighed and successively dried until a constant weight was reached. By knowing the oven dry weight of the litter per unit area and the drying curve, the evaporation from interception could be calculated. In this way they found that about 3% of the annual rainfall evaporated from the litter. But what they measured was not the flux, but the storage capacity. Another example of the first category was carried out by Putuhena and Cordery (1996). First, field measurements were carried out to determine the spatial variation of the different forest floor types. Second, the storage capacity of the different forest floor types were measured in the lab by using 10 a rainfall simulator. Finally, the lab experiments were extrapolated to the mapping step. In this way Putuhena and Cordery (1996) found average storage capacities of 2.8 mm for pine and 1.7 mm for eucalypt forest floors.

Examples of the second category are for example carried out by Pathak et al. (1985), who measured the weight of a sample tray before and after a rainfall event. They found litter interception values of 8%–12% of the net precipitation. But also here, they measured the storage capacity, rather than the flux. Schaap and Bouten (1997) measured the interception flux by the use of a lysimeter and found that 0.23 mmday-1 evaporated from a dense Douglas fir stand in early spring and summer. Examples of measurements with sheets were done for example by Li et al. (2000), who found that pebble mulch intercepts 17% of the gross precipitation. Miller et al. (1990) found comparable results (16–18%) for a mature coniferous plantation in Scotland.

Measuring forest floor interception

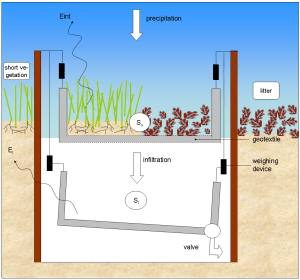

To measure evaporation from intercepted rainfall on the forest floor, a special device has been developed. The device consists of two aluminium basins, which are mounted above each other and are weighed accurately with 2 sets of 3 strain gauge sensors (see figure). One sensor consists of a metal ring where four strain gauges are mounted in the Wheatstone configuration. The upper basin is filled with forest floor and has a permeable bottom of geotextile, so water can percolate into the lower basin. In this lower basin a valve is installed, which empties every day for 10 min to avoid evaporation from the lower basin as much as possible. Also the space between the supporting structure and the aluminium basins is minimized, in order to avoid evaporation by turbulent wind fluxes. Besides the weight also the temperature is measured in one of the lower strain gauge casings. Every minute a measurement is carried out and saved on a data logger.

To calculate the amount of evaporation from interception a water balance is made of the interception device. When evaporation from the lower basin (El [L T-1]) is neglected and the weight of the lower basin is corrected for the drainage from the valve (Sl [L]), evaporation of intercepted rainfall (Eint [L T-1]) can be calculated as:

Eint(t) = Pnet(t) – [dSu/dt+dSl/dt]

where Su and Sl are respectively the storage of the upper and the lower basin [L], which are obtained by dividing the weight of the basins [M] by the density of water [M L-3] and the surface area [L2] of the basin.

This article came from Gerrits et al., 2006 [HESSD]

Papers on this topic:

Sadeghi, S.M.M., Aghajani, H., Jalilvand, H., Ahmady-Asbchin, S., Sadati, S.M., Coenders-Gerrits, M., Dymond, S.F., 2026. Canopy vitality drives rainfall redistribution in an old-growth temperate beech forest. Forest Ecology and Management 606, 123552. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2026.123552

Gordon, D. A. R., Coenders-Gerrits, M., Sellers, B. A., Sadeghi, S. M. M., and Van Stan II, J. T.: Rainfall interception and redistribution by a common North American understory and pasture forb, Eupatorium capillifolium (Lam. dogfennel), Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 24, 4587–4599, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-24-4587-2020, 2020.

Van Stan II JT, Coenders-Gerrits A.M.J., Dibble M, Bogeholz P, Norman Z. (2017) Effects of phenology and meteorological disturbance on litter rainfall interception for a Pinus elliottii stand in the Southeastern United States. Hydrological Processes, 31, 3719–3728. https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.11292

Tsiko, C.T., Makurira, H., Gerrits, A.M.J., and Savenije, H.H.G. (2012): Measuring forest floor and canopy interception in a savannah ecosystem, Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Vol. 47-48, 122-127

Gerrits, A.M.J. and Savenije, H.H.G. 2011. (invited) Forest floor interception. In Levia, D.F., Carlyle-Moses, D.E. and Tanaka, T. (Eds.), Forest Hydrology and Biogeochemistry: Synthesis of Past Research and Future Directions. Ecological Studies Series, No. 216, Springer-Verlag, Heidelberg, Germany.

Gerrits, A.M.J., Pfister, L., Savenije, H.H.G. (2010): Spatial and temporal variability of canopy and forest floor interception in a beech forest, Hydrological Processes, Vol 24, 3011–3025.

Gerrits, A.M.J., Savenije, H.H.G., Hoffmann, L. and Pfister, L. (2007): New technique to measure forest floor interception – an application in a beech forest in Luxembourg, Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 11, 695-701.